Normanton Down barrows from Byway 12 looking south across the Salisbury Plain.

For many people Stonehenge is a famous monument to visit on a trip to England. For others Stonehenge is a special place of spirituality, for quiet contemplation, communing with ancestors, for healing and celebration. It is also a place of archaeological and historical importance. This article, however, is an introduction to Stonehenge and its landscape: a unique prehistoric cultural World Heritage Site.

Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites’ was designated by UNESCO in 1986 as a World Heritage Site (WHS). The two parts of the WHS are around 25 miles (40km) apart, each about 10 square miles (26 sq.km) in area. The 1972 World Heritage Convention acknowledges WHSs to be of Outstanding Universal Value to mankind and commits the UK Government, as a signatory, to protection and conservation of the WHS and ensuring its transmission to future generations.

The WHS is described in a “Statement of Outstanding Universal Value” published on the website of UNESCO’s World Heritage Centre. It includes these statements:

“The World Heritage property Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites is internationally important for its complexes of outstanding prehistoric monuments. Stonehenge is the most architecturally sophisticated prehistoric stone circle in the world, while Avebury is the largest. Together with inter-related monuments, and their associated landscapes, they demonstrate Neolithic and Bronze Age ceremonial and mortuary practices resulting from around 2000 years of continuous use and monument building between circa 3700 and 1600 BC. As such they represent a unique embodiment of our collective heritage.

“There is an exceptional survival of prehistoric monuments and sites within the World Heritage property including settlements, burial grounds, and large constructions of earth and stone. Today, together with their settings, they form landscapes without parallel.

“The boundaries of the property capture the attributes that together convey Outstanding Universal Value at Stonehenge and Avebury. They contain the major Neolithic and Bronze Age monuments that exemplify the creative genius and technological skills for which the property is inscribed.

Key monuments at Stonehenge

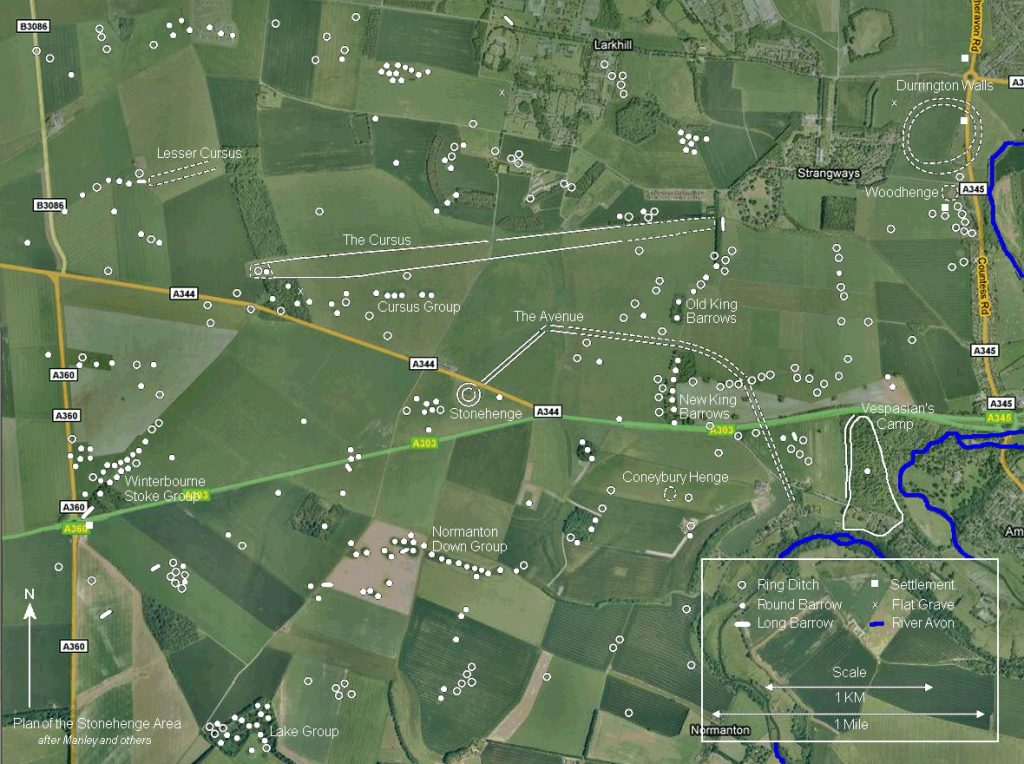

Google map layered to show key features described in Stonehenge landscape. Link to source

Precise dating of individual monuments is not always easy. Some were altered over many decades or more, others are placed within a broad cultural chronology. Monuments frequently mentioned in connection with the WHS include the following:

Early Neolithic period (c.3,700–3,300 BC)

The Cursus, to the north of Stonehenge, is an extensive linear bank and ditch earthwork, about 2 miles (about 3km) long and around 400ft (about 0.1km) wide. It was so-named for its resemblance to a Roman race track but its purpose is unknown. A smaller, Lesser Cursus lies further to the northwest.

The Cursus

Long barrows or burial mounds, so called because of their elongated form, are found across the Stonehenge landscape, sometimes forming an earlier element in groups of later round barrows of the Later Neolithic or Early Bronze Age. Most spectacular is the upstanding Winterbourne Stoke long barrow, beside Longbarrow Roundabout on the western boundary of the WHS. This fine monument lies at the head of a remarkable group of eight long barrows located around the head of a dry valley in the western part of the WHS, indicating that this was a place of special significance before the Stonehenge monument was built.

Robin Hood’s Ball, a ‘causewayed camp’ mentioned in the WHS Nomination document, but not included within the WHS, stands in a prominent location to the north of the WHS. This large earthwork is of lengths of bank and ditch broken broken at intervals by gaps or ‘causeways’. Windmill Hill causewayed camp at Avebury is of similar construction. Their use is not precisely known but they are thought to have been gathering places. Another causewayed camp has recently been found close to and outside the northeast boundary of the WHS, during archaeological evaluation prior to house construction.

Later Neolithic Period (c.3,300–2,200BC)

Henge monuments: A ‘henge’ in archaeological terms, is a roughly circular earthwork with a ditch usually on the inside of the bank and one or more entrances. There is more than one monument of this type in the WHS. The later large stone structures at Stonehenge and Avebury stand within ‘henge’ earthworks; that at Stonehenge is known to have pre-dated the erection of the megaliths.

The first Stonehenge began life as a cemetery with the original stone circle built 500 years before the version that we know today. In this video Professor Mike Parker Pearson re-evaluates the timeline of the construction of Stonehenge and sheds light on how it was used. Video by UCL Archaeology, 2013. 7.38mins.

Durrington Walls, close to the River Avon in the northeast corner of the WHS, is the largest earthwork henge in Britain. It is here that the only Neolithic village in southern Britain was found during excavation for the Stonehenge Riverside Project.

Woodhenge, is sited close to Durrington Walls, some 2 miles northeast of Stonehenge. A series of six concentric circles of wooden posts in the interior may have supported a roof. The post holes are now marked by low concrete posts. The purpose of Woodhenge is unknown but human burials were found in association with it.

The megalithic stone settings: The purpose of the large stone circles at Stonehenge and Avebury, at the heart of pre-existing ‘landscapes’ of earlier Neolithic monuments and sites, is still being debated. There is evidence which suggests that they had an astronomical purpose. The archaeological and historical records show that these exceptional monuments have been respected and used by succeeding generations to the present day, sometimes in association with human burials at Stonehenge. At Avebury, the West Kennet and Beckhampton Avenues were set with Sarsen megaliths.

The Avenue, an approximately 3km-long route between Stonehenge and the River Avon, was constructed during one of the later phases of the megalithic monument, c.2,200 BC. Defined by earth banks still partly upstanding near the henge, the Avenue is mainly only visible as ‘crop marks’ from the air. Another avenue in the Stonehenge landscape forms a short route between the henge at Durrington Walls and the River Avon and, it is suggested, might have provided a link to Stonehenge via the river and the Stonehenge Avenue.

The Cuckoo Stone, near Woodhenge, is an isolated megalith. Now recumbent, it was upright until at least the early 19th century.

The Early Bronze Age (c.2,400–1,600; overlaps with the Later Neolithic)

Round barrows: The latest megalithic phases of the Stonehenge monument seem to coincide with the apparently peaceful arrival of a new ‘Beaker’ people, characteristic for the introduction of metalworking and the wheel, their ‘beaker’ pottery and numerous round barrows or burial mounds, some of them, like Bush Barrow, containing rich grave goods. Round barrows were constructed in a variety of forms, including bell barrows, disc barrows and saucer barrows. There are hundreds of round barrows in the WHS, many still upstanding and some in spectacular groups along ridge tops where they were inter-visible with one another and, in some cases with Stonehenge: such as the Cursus Barrows and the Barrows on Normanton Down and King Barrow Ridge. The Winterbourne Stoke Barrow Group and the Normanton Down Barrows included and respected the alignments of earlier Neolithic long barrows, indicating some 2,000 years of continuous respect for the ancestors.

King Barrow Ridge on the horizon at sun rise during Open Access at the Spring Equinox in 2015.

Recent archaeological discoveries: A guided talk and walk – Part One

LISTEN to Simon Banton, an astroarchaeologist who has an intimate knowledge of the Stonehenge landscape. Last August, Simon walked us through the remarkable World Heritage Site and its wider setting to share his understanding of the recent discovery at Durrington Walls. He came up with some stunning conclusions that could resonate with indigenous societies even today. The first part of this experience is a recorded talk with illustrations, maps and transcript accessed here on this page.

Part two will be a video.

Blick Mead and the Mesolithic period (c.7,500–3,700 BC)

In recent years, the remarkable site of Blick Mead, beside the River Avon on the eastern side of the WHS, has yielded an astonishing wealth of flint tools and other evidence of use of the WHS long before the Neolithic and Bronze Ages for which the WHS was designated and became famous. It appears that Blick Mead was in use by hunter-gatherers and possibly the first settlers in this landscape and also provides significant evidence of continuous occupation into later times of what is today a WHS of unparalleled significance.

In the last two decades or so, a number of archaeological excavations have taken place in the WHS: for example, at Durrington Walls, Woodhenge, and on the Stonehenge Avenue, in attempts to answer questions about the Stonehenge landscape and those who created and lived in it in prehistoric times.

With advances in technology, much geophysical survey work has also been undertaken. A fascinating LiDAR survey video, produced by Wessex Archaeology, maps changes in WHS ground level from the shape of the land to low archaeological features and more prominent, peak-like images from buildings and trees. The Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes Project (see video also, here) has revealed a very substantial number of new archaeological sites within the WHS, yet to be fully analysed.

There is an enormous amount yet to be learned about the WHS, much of it still hidden from the naked eye but far more important to our understanding of this special place.

Below is a gentle 10 minute flight across Stonehenge in its World Heritage landscape published by Megalithomania.co.uk in June 2016.

Further information

Obviously, a great deal has been published on Stonehenge and its landscape. A brief introduction produced by English Heritage, with links to further information, can be seen here. Another introductory video, by the National Trust, can be seen here.

A more detailed summary by Tim Darvill, with references for further reading, was prepared for the Royal Archaeological Institute in 2017.

Part 1 of The Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites Management Plan, has longer sections on the outstanding universal value and other values of the WHS and a good range of images of key monuments. It also sets out the commitment of those who endorsed the Plan to ensuring the effective protection, conservation and presentation of the WHS and its transmission to future generations.

Take Action!

Please help us save this outstanding landscape from the bulldozer to build a 4-lane dual carriageway and tunnel. Take action here.