Presentation by Professor Mike Parker Pearson

Saving Stonehenge World Heritage Site

Stonehenge Alliance webinar on 3 June 2021 NOTE 1

Presentation by Professor Mike Parker Pearson

KEY POINTS

Current position:

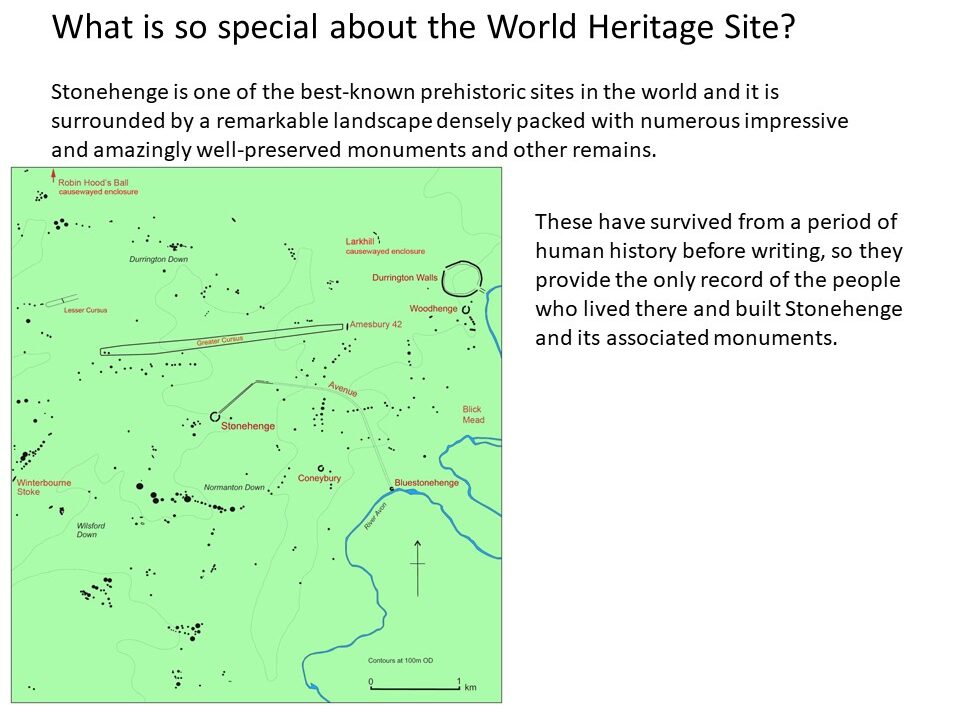

- This is a landscape packed with many impressive standing monuments and also below ground.

- This landscape represents a period of our history for which we have no written records. Consequently, the remains are the only source of information.

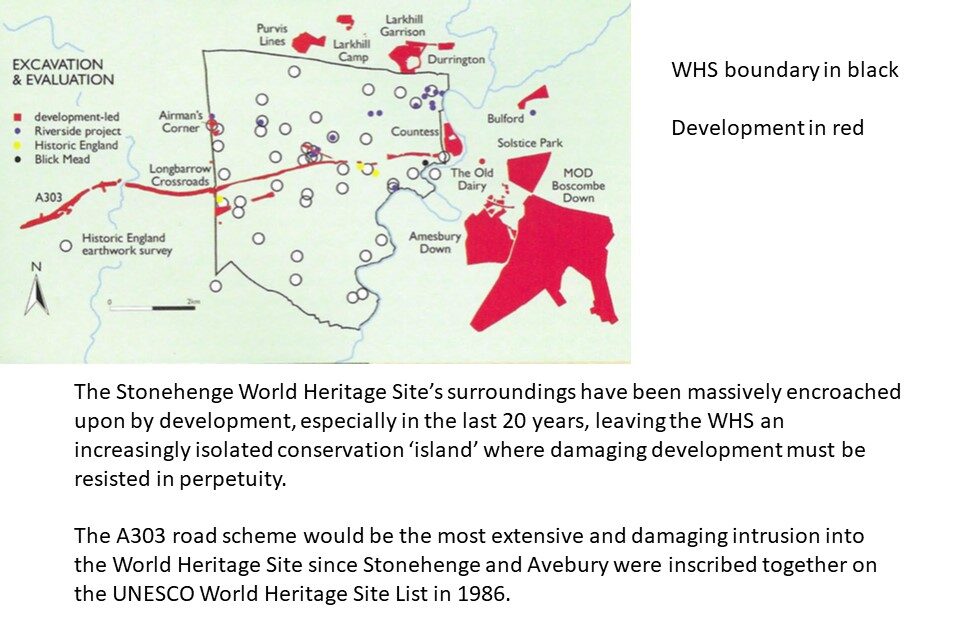

- The World Heritage Site is within an area that’s been massively encroached upon in the last 20 years. What is left is an island of conservation where damaging development must be resisted in perpetuity.

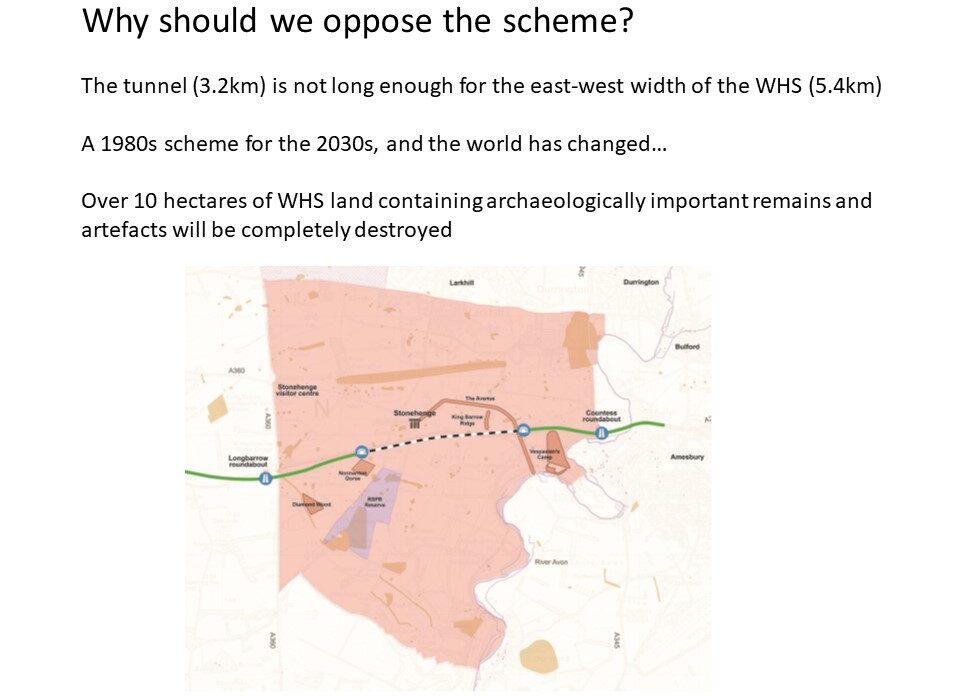

- This is a 1980s scheme for the 2030s, and the world has changed.

Scale and landscape:

- The tunnels are not long enough. 3.2 kilometres when the World Heritage Site is over five kilometres across at that point.

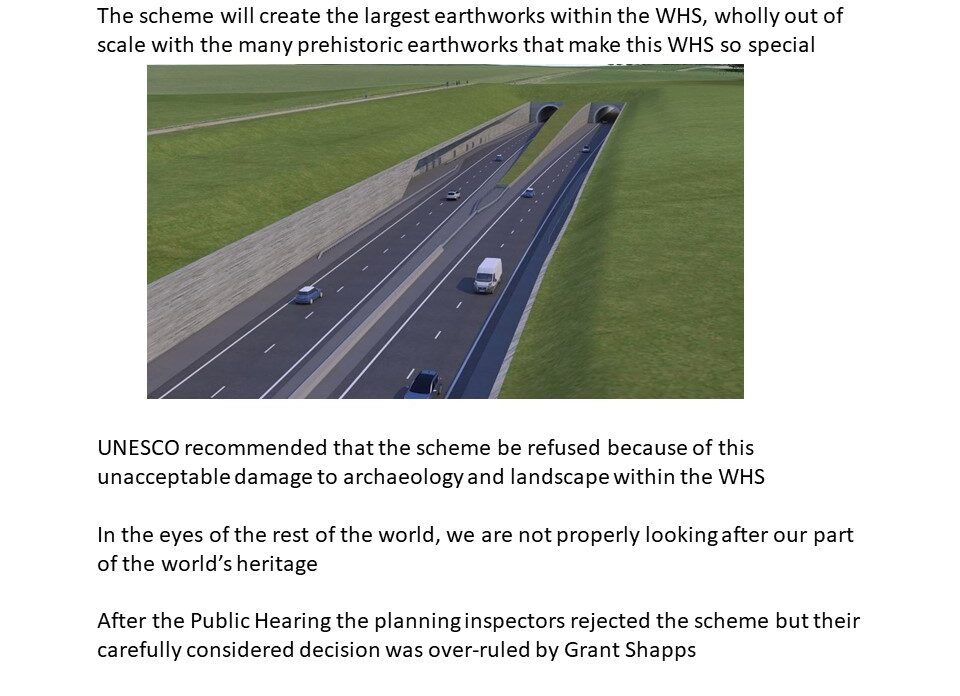

- The earthworks produced by the new scheme will completely dwarf those of the world heritage site itself.

- UNESCO recommended that the scheme be refused because of unacceptable damage to archaeology and negative impact on the landscape.

Ploughsoil:

- The road will cut through an unusually high density of prehistoric artefacts and buried features within the ploughsoil.

- People lived their lives on the surface. To properly understand what they were doing in successive periods of prehistory, from the Mesolithic through to the Bronze Age, intensively sampling the ploughsoil is necessary i.e. using shovels, spades and sieving the soil in metre squares.

Loss of artefacts:

- Research standards insisted on by Historic England and National Trust within the WHS over the last 10 years were refused by Highways England, even though this was advised by the Scientific Committee.

- Highways England’s approach is to strip the surface and then record what has actually survived beneath the ploughsoil. Only a miniscule proportion of the total remains will be found.

- Over half a million worked flints as well as likely prehistoric artefacts within the ploughsoil will be bulldozed without record or recovery.

Reputation:

- Highways England’s approach is in flagrant breach of the usual standards met by research excavations in the WHS in which sampling may be as high as 100%.

- In the eyes of the rest of the world, we’re not properly looking after our particular bit of the planet’s world heritage.

- The lack of concern contributes to the UK’s declining reputation for protection of the historic environment.

Video recording of presentation

19:09 minutes

Transcript with slides

Tom Holland (NOTE 2) Let’s hear now from Professor Mike Pearson. No better person to tell us why the road scheme that Kate has just been demonstrating and illustrating, why it would be so damaging in archaeological terms. So, Mike, thanks very much for coming here. Hugely grateful. Over to you. Mike Parker Pearson (NOTE 3)

Archaeological aspects of the A303 Stonehenge Road Scheme 0:22

I want to start off with a series of questions about the archaeology, based on some of the questions that have already come in.

- What is so special about the world heritage site?

- Why should we oppose the scheme?

- What do we know about the archaeology that would be lost?

- Isn’t the archaeology in fact all going to be recorded before the road is constructed?

- Why are some archaeologists actually in favour of the scheme?

SLIDE 1

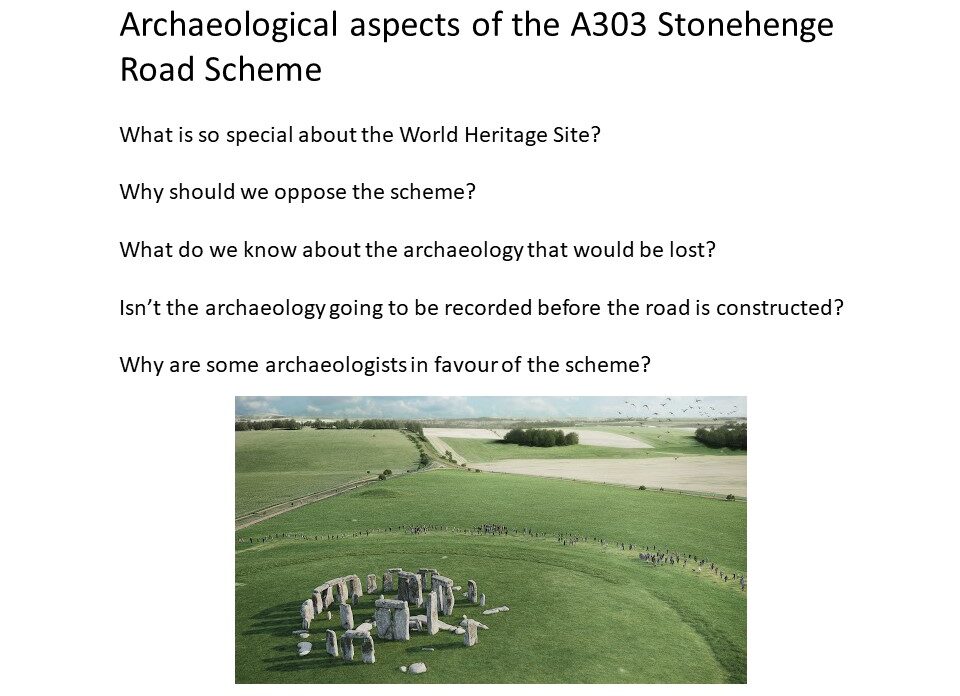

Of course, it’s not just Stonehenge, it’s the fact that this is a landscape packed with many impressive standing monuments, in particular, but also below ground, There are not just hundreds but thousands, in fact millions of archaeological artefacts and other remains. Hardly a year goes by without some major discovery being made within the World Heritage Site that hits the international news. Of course, this is a period of our history for which we have no written records and, consequently, the remains themselves are the only source of information. So they are extremely precious because, once they are gone, they are gone for good.

SLIDE 2

I think we have to remember that the World Heritage Site is within an area that’s been massively encroached upon in the last 20 years. What is left is really an island of conservation which is now the World Heritage Site. So damaging development within that island really has to be resisted, not just in the meantime but in perpetuity. And, unfortunately, the road scheme would indeed be the most extensive and damaging intrusion since the inscription of Stonehenge and Avebury together on the World Heritage Site List in 1986.

What is so special about the World Heritage Site? 1:00

SLIDE 3

Why we should oppose the scheme 2:53

Very simply, the tunnel is just not long enough: 3.2 kilometres. The World Heritage Site is over five kilometres across at that point.

It’s a very out of date scheme, I’m afraid. I was there at English Heritage in the late 1980s when it was dreamed up. And here we are – what, 50 years later – or it will be 50 years later, when it actually becomes operational. And I’m afraid the world has changed in so many ways that we’re all aware of. And we have to wonder whether this really is the most suitable way of solving the problems that were perceived in the 1980s.

From the archaeology, the most important thing is that that road line will ensure the complete destruction of 10 hectares of the World Heritage Site, most of it in the two stretches outside of the western and eastern portals, where the tunnel emerges.

But also, the corner at the top left, the northwest corner of the World Heritage Site, is also going to be damaged by road building. And the thing about it, as you saw from Kate’s pictures, it’s a total destruction, nothing will be left. Very different to all the excavations that have taken place for research in the World Heritage Site because everything there is simply put back. What isn’t taken away for the museum actually goes back in the ground broadly in the place where it came out of.

SLIDE 4

What makes Stonehenge so special? 4:40

[It] is its archaeology and its earthworks, amongst other things. Kate’s already made the point that the earthworks produced by the new scheme will completely dwarf those of the World Heritage Site itself. As already has been mentioned, UNESCO recommended that the scheme be refused because of unacceptable damage to archaeology and negative impact on the landscape. And I’m afraid what this means is that, in the eyes of the rest of the world, we’re not properly looking after our particular bit of the planet’s world heritage. And as already explained, it [was a recommendation] that the planning permission was indeed refused, only to be overturned.

SLIDE 5

What do we know about the archaeology that would be lost? 5:39

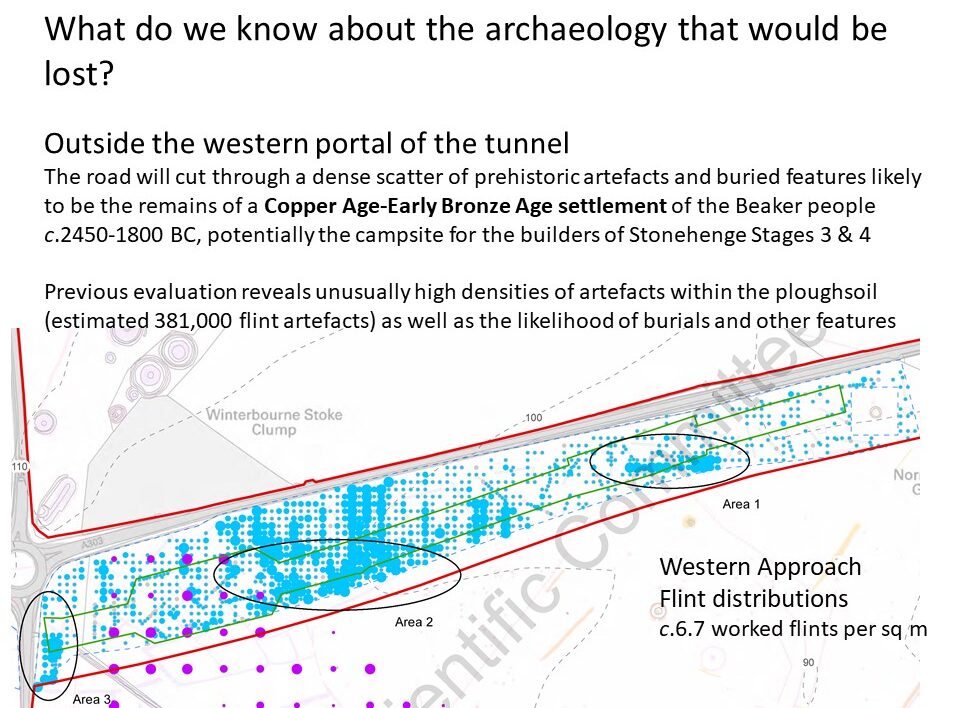

Outside of the western portal, evaluation work done by contractors for Highways England, just looking at the ploughsoil, produced many thousands of artefacts. They’re marked in this map here, in blue. So, the sizes of the blobs indicate the densities of finds, mostly struck flint, flint artefacts and flint tools. And the density is quite staggering, as you can see, in several areas. The road line is the area marked in green. What we know from this is that, not only from their sampling – their 1% sample of that ploughsoil – we can reckon that there will be 381,000 prehistoric flint artefacts that will simply be destroyed, machined off, before the actual excavation of what’s underneath the ploughsoil takes place.

We know from preliminary analysis of these finds that a good number of them are the remains of a settlement of the period that we call the Copper Age and the Early Bronze Age. So this would be an area of settlement of people in prehistory that we know as the Beaker people. And, potentially, this was their campsite when they were building the later stages of Stonehenge, stages three and four, around 2000 BC.

SLIDE 6

Eastern portal and Blick Mead 7:28

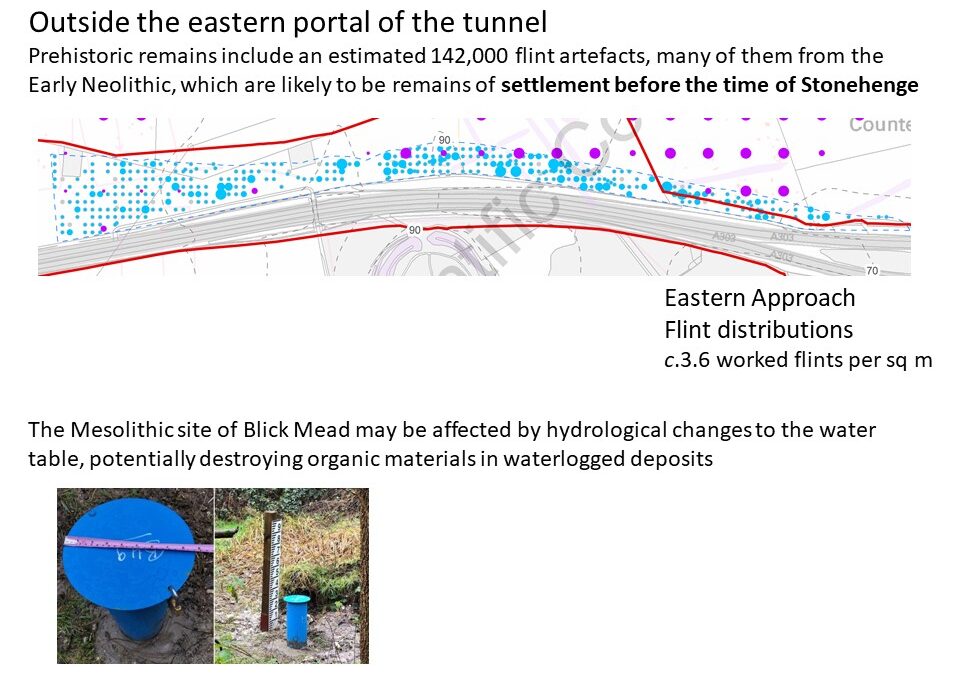

Outside the eastern portal, the densities are not quite so great. But the material recovered indicates that a lot of it derives from a period where we know very little – well, virtually nothing I have to say – about settlement in the Stonehenge landscape. And this is from the early Neolithic. This is from the time that they were building long barrows and, in fact, the western [A303 widening] route is passing through the densest cluster of Neolithic long barrows anywhere in Britain.

So, the settlement on the eastern side may be really very important. And again, an estimated 142,000 flint artefacts in the ploughsoil, under the current proposals for investigation, are simply going to be bulldozed.

Further out to the east [is] the Mesolithic site of Blick Mead. Although it is physically not affected, there is concern that the construction will create, of course, hydrological changes, lowering the water table; and there is worry that, potentially, organic deposits will be destroyed: that materials that are in deposits that are currently waterlogged may end up drying out and vanishing.

SLIDE 7

Rollestone Corner 9:01

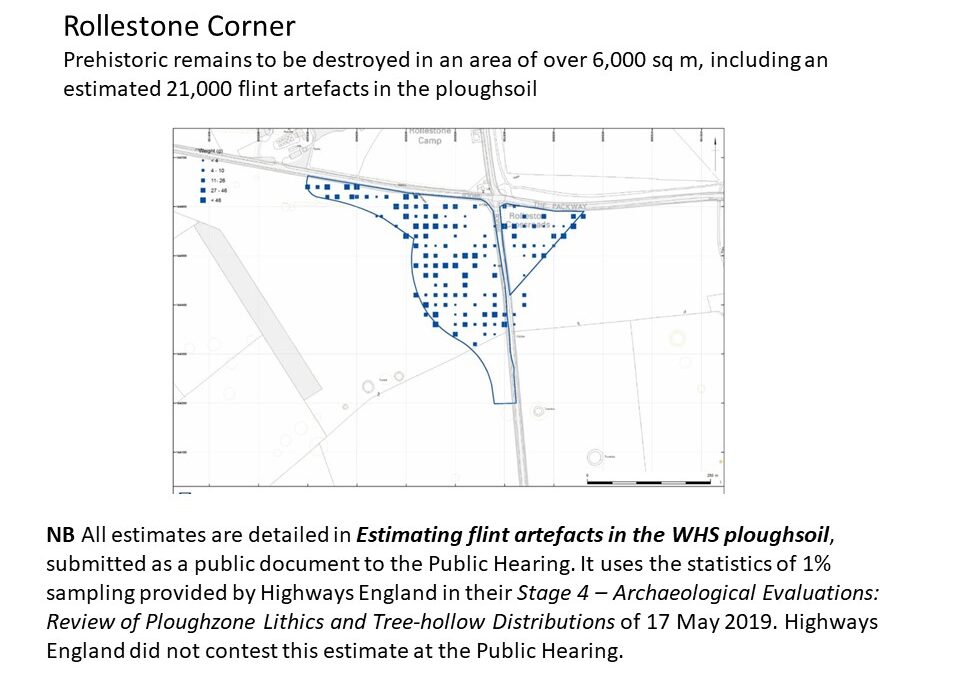

And then, finally, the third area: a much smaller one right up in the top northwest corner and relatively small damage, but nonetheless 21,000 flint artefacts in the ploughsoil.

SLIDE 8

Why are finds in the ploughsoil so important? 9:22

For those of us who work with prehistory, the time of Stonehenge is a time when actually people in the main weren’t digging pits and ditches. They were living their lives on the ground surface, living in ephemeral houses and leaving few holes into the ground: the occasional grave, the occasional pit, maybe a tree hole where a tree had blown over, dumping material in there or using it as a working area. For most of their life and work was conducted on the surface. And of course, those layers have all been ploughed and all of the finds from those activities are in that ploughsoil.

So, we as archaeologists working within the World Heritage Site have known that to really understand what they were doing in the successive periods of prehistory from the Mesolithic through to the Bronze Age, you have to intensively sample that ploughsoil. And that means getting out there with shovels and spades and sieves and sieving the soil in metre squares to actually extract all of the artefacts. And then you can plot out, metre by metre, the distributions to give you a picture of how people lived in that landscape and how that changed through time. It’s only through doing that really detailed work that you’ll get that.

Unfortunately, the Highways Agency’s (NOTE 4) approach is basically to strip and then record what has actually survived beneath the ploughsoil. And I’m afraid that is a miniscule proportion of the total remains.

Now they were advised by the Scientific Committee that was appointed, that equivalent standards should be applied to their work as to anyone else working in the World Heritage Site. They refused to do this. They considered it expensive, that it would take too long even though such a process could be mechanised. And the result is that they are prepared to pay for sampling that will only be minimal and we will see half a million worked flints and other prehistoric artefacts lost without recovery. Worst of all, they’re just going to be scattered over various parts of the World Heritage Site completely out of context. It’s an unacceptable level of damage.

SLIDE 9

Isn’t the archaeology going to be recorded before the road is constructed? 12:18

The contract company that won the contract, Wessex Archaeology, are indeed among the best archaeological contractors in the world, and I’ve every confidence that they’ll do an excellent job if they can recruit enough staff. At the moment, we’re somewhere around 1,000 people short for working in commercial archaeology in Britain due to the current political circumstances with Europe.

But however good Wessex are, they can only do as much as they’re allowed by the brief that they’ve been given by Highways England and by the heritage agencies who have been backing the scheme with the Department of Transport since the 1980s.

They’re not going to be required to map or recover the majority of artefacts. They have so far recovered just 1 per cent; they’re talking about levels of percentage under 10, no more than 12 ½ per cent, for the rest of the work . But it shouldn’t just be the ploughsoil.

Highways are not prepared to ask for even all of the sub-surface features to be excavated, notably the tree hollows, which may contain prehistoric remains. They’re only going to look at just 12 ½ per cent of those, not the 100 per cent that many of us would recommend.

I’m afraid this is a flagrant breach of the usual standards that are met by archaeologists working in the World Heritage Site.

SLIDE 10

Example of total or near-total recovery compared with lower percentage recovery 14:09

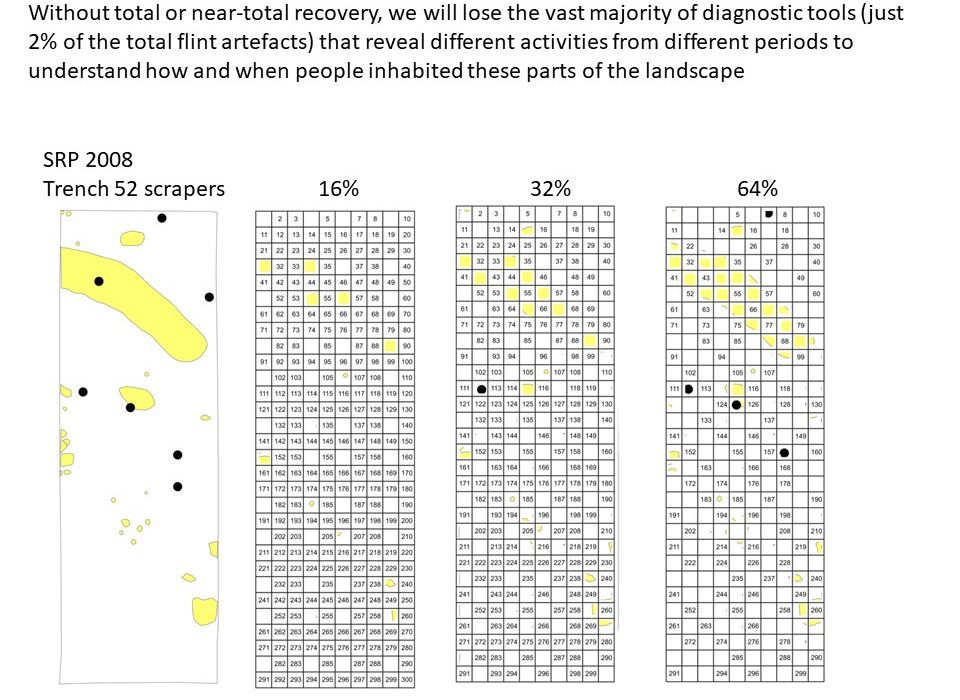

Just to give you an example of what this means in archaeological terms. We were working on a number of sites between Stonehenge and the western portal back in 2008, and I just take an example that I’ve worked up from just one of our trenches. It was 30 metres long by 10 metres wide. So that is 300 one-metre squares.

We hand dug and sieved every single square. That’s what we were required to do by English Heritage and the National Trust. These are their requirements that they didn’t require Highways England to abide by.

I plotted out the distribution of what we call the diagnostic tools. Now, these are the tools that are really important because these tell us the date of activity. And they’re also diagnostic of the type of activities carried out. In this case, we’re looking at Bronze Age scrapers, Bronze Age flint scrapers. And you can see on the left-hand side, we actually recovered seven of them within that area. Now, they constitute something like 2% of the total flint artefacts.

If we were to sample at 16%, which is already higher than Highways England are prepared to ask the contractors to do, we wouldn’t have found any of them. Even if we sampled a third of the area, we’re only likely to find just one. And even well over 50% at 64%, you can see we picked up four.

So, only at that point, would we be beginning to get an idea of the diagnostic material and what it tells us about the date and the type of activities. Of course, scrapers were used for cleaning hides, amongst other things.

SLIDE 11

Why are some archaeologists in favour of the scheme? 16:18

There’s no doubt that some think that a short tunnel is better than no tunnel and that we should just settle for the compromise, close our eyes to the archaeological damage, and bite the bullet.

Some think it’s entirely acceptable to lose over half a million flint artefacts in the ploughsoil and I think it can only be because they don’t understand that there’s valuable information on the spatial and chronological distribution of activities of the prehistoric people who lived in the landscape.

Others say “Well, we’re going to do – 1, 2, 3, 4 per cent sampling”. It’s not adequate, because you have to do high percentage sampling to recover enough of those rare diagnostic artefacts, as I explained with the previous slide.

Some also say that the short tunnel is better than the longer but cheaper surface route, or going round the south of the World Heritage Site and avoiding it there. But as far as we know, there is no significant archaeology in that area at all.

And finally, and I think this is quite an important reason: there are archaeologists who don’t want to rock the boat. They don’t want to jeopardise their standing with the heritage agencies. Many of them are consultants and they live in part off consultancy work. And we should also remember that none of the archaeologists who work for the heritage agencies who are working together with Highways England can even risk saying what they really think of this scheme. As you know, these organisations have been shedding jobs, such as the National Trust and English Heritage.

I’m afraid it is very sad but their lack of concern I think has undoubtedly contributed further to our declining reputation for being able to protect not just our historic environment. Remember, this is the historic environment for the World.

SLIDE 12

NOTES

- Saving Stonehenge World Heritage Site webinar on 3 June recorded here.

- Tom Holland is Stonehenge Alliance President, webinar chair, and an award-winning historian and broadcaster.

- Mike Parker Pearson is Professor of British Later Prehistory at the Institute of Archaeology, UCL. He was director of the Stonehenge Riverside Project that worked to situate Stonehenge within the archaeology of the surrounding landscape, and his thesis that the Blue Stones came from a dismantled Neolithic stone circle in Pembrokeshire recently made headlines around the world. Professor Parker Pearson is a member of the Scientific Committee for the A303 Stonehenge scheme.

- Highways Agency was converted into Highways England in 2015 as an executive non-departmental public body, sponsored by the Department for Transport.