Presentation by Professor Phil Goodwin

Saving Stonehenge World Heritage Site

Stonehenge Alliance webinar on 3 June 2021

Stonehenge-A303 Amesbury to Berwick Down: The Highways England Appraisal

Phil Goodwin, Emeritus Professor of Transport Policy, UCL and UWE; Senior Fellow, Foundation for Integrated Transport.

Video recording of presentation

18:26 minutes

NOTE: This document consists of the speaking notes and slides prepared for the presentation. It is close but not identical in every respect to the words used in the live event. References are given in the last slide. Presentation & notes by Professor Phil Goodwin as pdf

As an introduction I should explain that I have worked in the field of transport appraisal for about 40 years, and I have been heavily critical of the many built-in biases which, I argue, tend to favour the wrong projects. But the core of my argument today is quite different. I am going to put aside my general criticisms, and argue a different case.

HE = Highways England

I argue that even if we accept every single word of the Highways England appraisal, and method, and assumptions, the scheme as a road scheme does not make sense. And even if we accept every single word of the method used to assess the Heritage benefits of the project then it still doesn’t make sense. So I’m going to prove this using only the official numbers.

BCR = Benefit Cost Ratio

First, let’s just think of it as a typical road scheme. What does Highways England tell us about the benefits of this? The transport function of the scheme is to provide more road capacity on the A303 to cope with Highways England’s own forecasts of rising traffic, mostly cars, every year for decades.

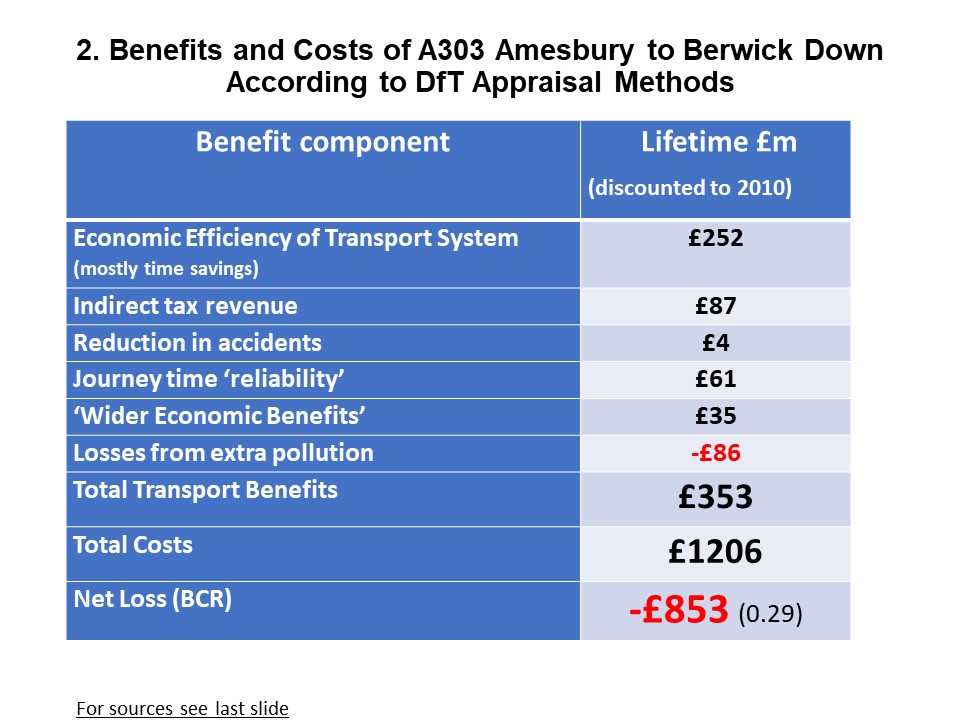

The biggest estimates of benefit will be the cash value of all the estimated time savings, on millions of journeys over 60 years. That adds up to £252 million worth. Then there are some tax benefits, some claimed reductions in accidents (they are not worth so much), more reliable journeys, a little contribution to economic growth, a small amount to be taken off for pollution. Total benefits of £353 million, which sounds a lot but the estimated costs of the scheme, at £1206 million – £1.2 billion – are over three times larger than the benefits. As a transport project, the scheme makes a loss to society of £853m.

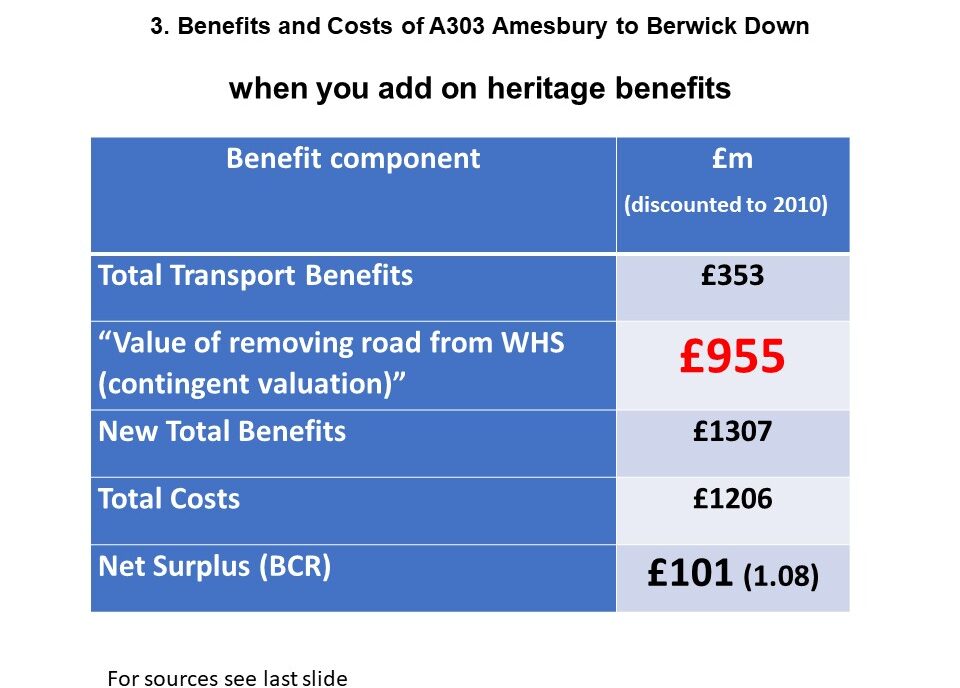

But then, if it was just a road building scheme, you would not build a tunnel. Tunnels are far too expensive. The reason for the tunnel, Highways England tell us, is to protect the World Heritage Site from traffic. So an amount was added, for the estimated cash value of the protection of the heritage. This amounts to £955m, just under a billion pounds, for the heritage benefits of removing the road from the World Heritage Site, and now the scheme makes a surplus, a profit. I should say that it’s only just a surplus. For those who like benefit cost ratios, 1.08 is not considered a good return on investment, over 60 years, and most schemes reporting these results would not get funded.

£955 million is the key number in the whole calculation. By good fortune, this is bigger than the transport loss of £853. So where did it come from?

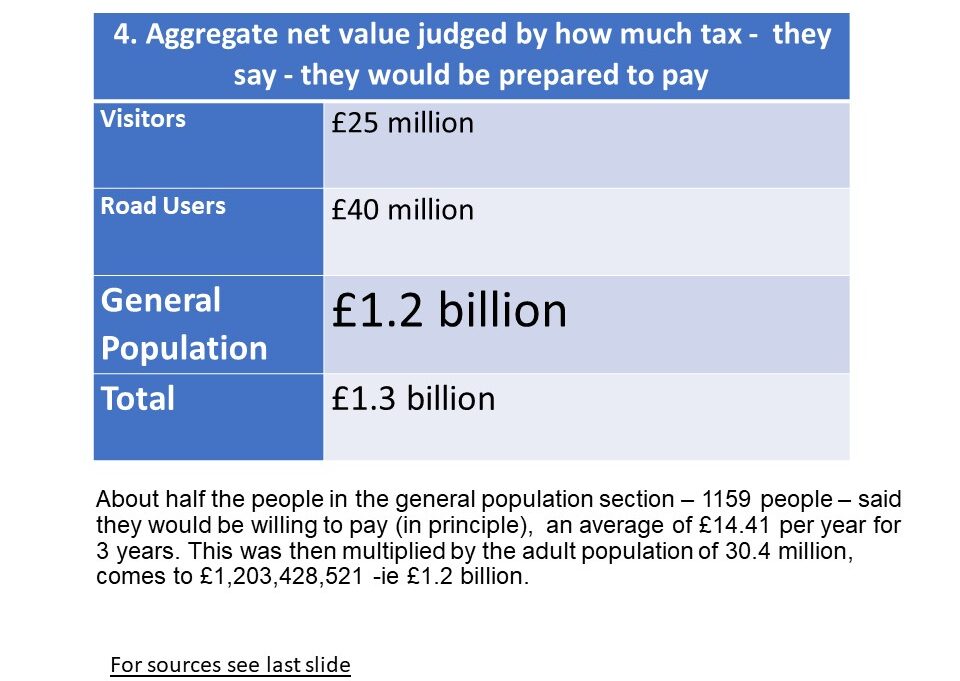

Highways England commissioned a survey: some face to face interviews with visitors, but mostly on-line surveys, on the internet, with a sample of local residents taken as the people who drive past the site and enjoy the view, and a bigger sample representing the ‘general population’ spread over the whole country.

This survey asked people ‘if they would, in principle, be willing to pay an increase in annual taxes over a three year period to support the road scheme’. If they said no, they were asked ‘if the proposed road scheme would reduce their life satisfaction, and if so how much would be ‘minimum they would accept in compensation’

It was made clear that they would not be asked to actually pay this tax, and they certainly wouldn’t receive the compensation. It was hypothetical. (It was the sort of question that politician would generally reply ‘I don’t answer hypothetical questions’). But the public are more amenable and most gave answers. The report says that this represents the value that the improvements achieved by the road scheme will have for users and non-users of the world heritage site.

About half the people in the general population section – 1159 people – said they would be willing to pay (in principle), an average of £14.41 per year for 3 years. This was then multiplied by the adult population of 30.4 million, which comes to £1,203,428,521 -ie £1.2 billion. (This is then discounted back to 2010 prices to give the £955m in the previous table).

There were separate answers for the visitors and the local drivers; being few in number, the total notional tax revenue to be collected from them is small. The big notional revenue was from the ‘general’ sample, their individual values being multiplied by the whole adult population of the UK. These of course include the people who were not expecting ever to visit the site, or pass near it, but wanted to protect it.

Now I guess some of you are thinking that this is a very dubious calculation, and it’s true that it can be seriously criticised, on technical grounds. There is not time now to explain those criticisms, but we can go into it later if you want. It was these criticisms which made the Inspectors appointed by Secretary of State call the answers ‘inherently uncertain’.

But bear with me, I’m still accepting the calculations put forward by Highways England. We do not need to resolve those troubling objections, for one key reason. Among the 1500 documents of the inquiry, we now have another one, which is the most important of all, and that is the Inspectors report.

ExA = Examining Authority (ie inspectors)

That is a statement of considerable status in planning law. The Secretary of State can overrule it, subject to certain conditions which are currently a matter of legal dispute, but it has a continuing official status as the official document which the whole public examination system is directed to produce.

In summary, the Examining Authority concluded that the scheme would substantially harm the integrity and the authenticity of the world heritage site, causing permanent irreversible damage, affecting not only our own, but also future generations. Now my point is not whether this is right or wrong. It is that this statement itself profoundly changes the interpretation one can put on the results of the contingent valuation estimate of the heritage value of the site.

This is because the answers that were given were to hypothetical questions about how much people would be willing to pay in hypothetical taxes for a project which

“removed the sight and sound of the road from the vicinity of Stonehenge”, and

“represent the value that the improvements achieved by the road scheme will have for users and non-users of the WHS. They are a key component of the overall cost-benefit analysis of the scheme”

But this extra value is estimated by a procedure called ‘contingent valuation’

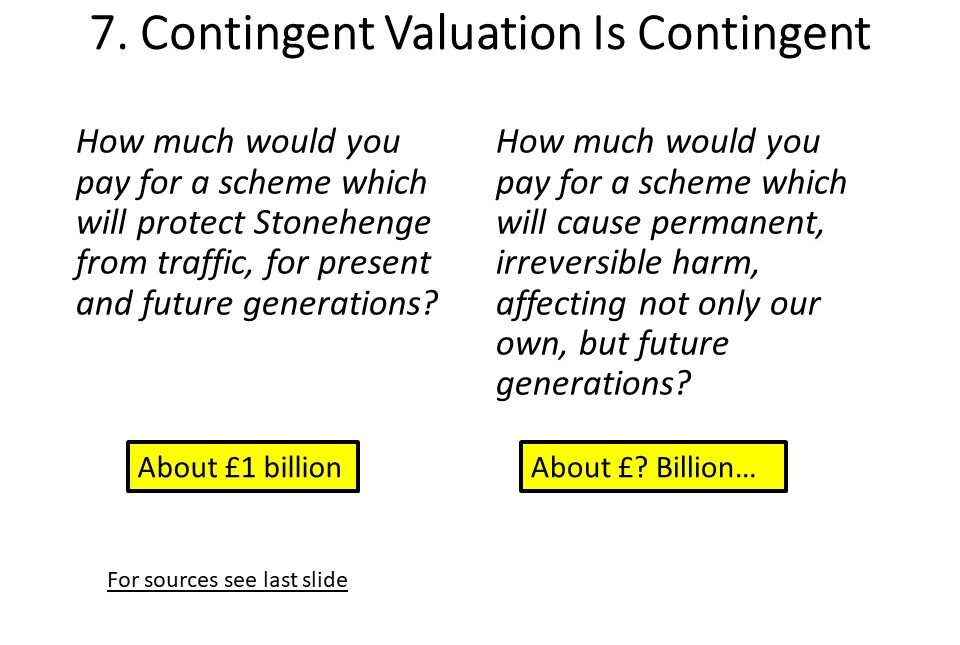

And the whole point is that contingent valuation is contingent – it depends on what information and hypothetical conditions are offered to the respondents.

We know what the answers were for a question, what would you pay in taxes for a road scheme which would protect Stonehenge for present and future generations. At that date, the details of the scheme were not known. What was known about the scheme was that its promoters stated it would protect the world heritage site. We now know something else about the scheme, which is also a key part of the official library in the appraisal, namely the Examiners’ Report.

So we can make a mind experiment. Imagine that the question was ‘how much would you be prepared to pay in taxes for a scheme which would cause irreparable long term damage to the World Heritage Site for present and future generations?’. Or, to leave it more open, how much for a scheme that ‘the Planning Inspectors had said’ that such damage would be caused.

The mind experiment is this: would that have made a significant and substantial difference to the results of the survey? Everybody working in this field accepts that the values produced are sensitive to the way the question is presented.

I would assert that it would certainly have reduced the reported willingness to pay by between 50% and 100%, and possibly even reversed the ‘willingness to pay’ and ‘willingness to accept compensation’ so that the heritage benefit to insert into the benefit cost appraisal would have a substantial negative value.

In saying this, I would be implicitly accepting the entire rationale of the Highways England methodology, and only adding one element, which is a true statement about what the Inspectors had concluded. I am asserting that that way of framing the question would very substantially change the answer.

Some assertations about the future are inherently uncertain, and cannot be proved one way or another. My assertion is not uncertain in this sense, because it is not about the future. It can be tested, empirically, by means of another survey. This survey would cost much less than the first, since it would not need all the setting up and design costs. All other elements of the survey would stay the same: it is only the framing of the core question which changes, giving respondents one more piece of information, factual information, of what the Inspectors had said.

We know the result already of what people said given the information that the scheme would benefit the site. The mind experiment is to ask ourselves what we – and they – would say if given the information that it would not benefit the site.

So I conclude that the work already done

- demonstrates that the scheme would not provide transport benefits nearly equivalent to its cost, and

- (according to my assertion, professional judgement based on some 40 years engagement with road appraisal methods), that the method has not demonstrated that it would provide heritage benefits which would make up the difference.

My point is that you do not have to agree with my judgement, because whether I am right or wrong can be tested within a couple of months at the cost of a few thousand pounds. Let us do that test – openly, transparently, with participation of both sides of the argument. We could ask the DfT’s technical appraisal people, and their Advisers, to be involved. I’d volunteer to be on the Steering Committee for a project like that, and I’m sure that dozens of other serious experts would as well.

All this would not resolve the wider problems of the UK’s transport strategy and appraisal systems. They still apply. But it does make a contribution to address this project, which is unique in not even passing its promoters’ own criteria.

REFERENCES

All figures and quotes are from documents of the Examination Library held by the Planning Inspectorate. It contains 1496 documents, and an index is available, with free access, at https://infrastructure.planninginspectorate.gov.uk/projects/south-west/a303-stonehenge/?ipcsection=docs

Slide 1: Mine

Slides 2 and 3: Extracted from Tables 5.5 and 5.6 in https://infrastructure.planninginspectorate.gov.uk/wp-content/ipc/uploads/projects/TR010025/TR010025-000447-7-1-Case-for-the-Scheme.pdf

Slide 4: Table and text from Para 1.1.10 and para 1.1.17 with its unnumbered table in https://infrastructure.planninginspectorate.gov.uk/wp-content/ipc/uploads/projects/TR010025/TR010025-000455-7-5-ComMA-Appendix-D.pdf

Slide 5: Cover page and para 7.2.32 of https://infrastructure.planninginspectorate.gov.uk/wp-content/ipc/uploads/projects/TR010025/TR010025-002181-STON%20%E2%80%93%20Final%20Recommendation%20Report.pdf

Slide 6: First quote from para 5.3.13 of https://infrastructure.planninginspectorate.gov.uk/wp-content/ipc/uploads/projects/TR010025/TR010025-000447-7-1-Case-for-the-Scheme.pdf

Second quote from para 9.1.2 of https://infrastructure.planninginspectorate.gov.uk/wp-content/ipc/uploads/projects/TR010025/TR010025-000455-7-5-ComMA-Appendix-D.pdf

Slides 7 and 8: Mine

Please share