Simon Banton

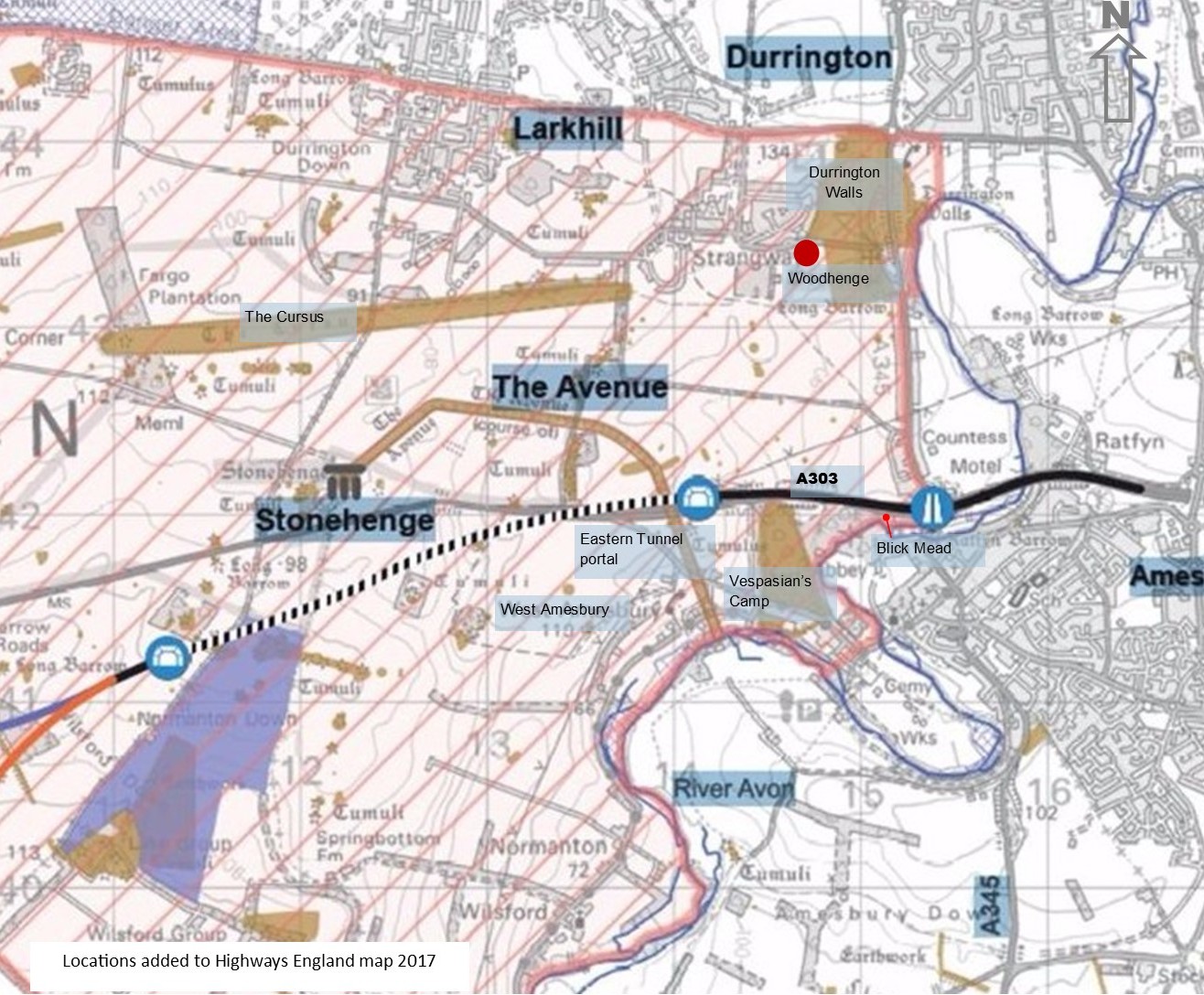

Last summer the Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes team discovered a vast ring of twenty massive 4,500 year old shafts surrounding Durrington Walls and Woodhenge. The major discovery within the Stonehenge World Heritage Site, close to the proposed road widening scheme caused the UK Government’s Transport Secretary, Grant Shapps MP, to defer his decision on whether to build the Stonehenge Tunnel to November. The entrance to the eastern tunnel portal would be very close and “further consultation” was required to allow for further analysis.

Simon Banton, an astroarchaeologist who has an intimate knowledge of the Stonehenge landscape walked us through the remarkable World Heritage Site and its wider setting to share his understanding of the recent discovery. He decided to reference the new finds in relation to the physical landscape features rather than fathom the plans, and came up with some stunning conclusions that could resonate with indigenous societies even today.

Simon described his thoughts in a blog which we later asked him to walk and talk us through on the ground with a small group last August.

First, however, Simon needed to explain the context of these finds by referencing the 180 degree sweep of the eastern horizon in some detail so that visitors could understand his view points. You can follow the transcript of the detailed introductory commentary, images and maps as Simon guides you through the physical features making it an important record of the eastern setting of the World heritage Site.

Commentary by Simon Banton

LISTEN to Simon’s commentary

i) Welcome and introduction 2:23 mins

ii) Commentary continued 19:41 mins

Illustrated transcript

READ the transcript with maps, illustrations and links.

Red dot marks Simon’s view point. Click to enlarge.

Hello everybody. And welcome to the Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage Site. And we’re in the Stonehenge part of that. 26 square kilometres of preserved and honoured landscape that we are privileged to have mostly intact at the moment and we’re standing in a position a little bit west of Woodhenge, and a little bit south of Durrington Walls looking out over the eastern horizon.

And the reason that we are standing here and looking that way is to do with the recent discovery of a series of enormous pits that surround Durrington Walls and Woodhenge. And by enormous, I mean there are twenty of them each about 20 meters in diameter and five meters or more deep in a circle. A rough circle. A pretty good rough circle it has to be said, in a radius of about one kilometre. The centre of that circle of pits being in the centre of Durrington Walls Henge.

Yellow dots mark the location of the shafts, or giant pits. Picture: University of St Andrews/PA Wire

And this is a recently published discovery by the Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes team who re-analysed some of their geophys research of the area that they had taken over the last several years. They had noticed this regular pattern of anomalies which, if they proved to be right, whether human made or embellished by humans of natural features, could quite possibly be landscape engineering on an epic scale, and we’ll talk a little bit more about what they might be for, or what they seem to frame, as we go a little further round on this walk.

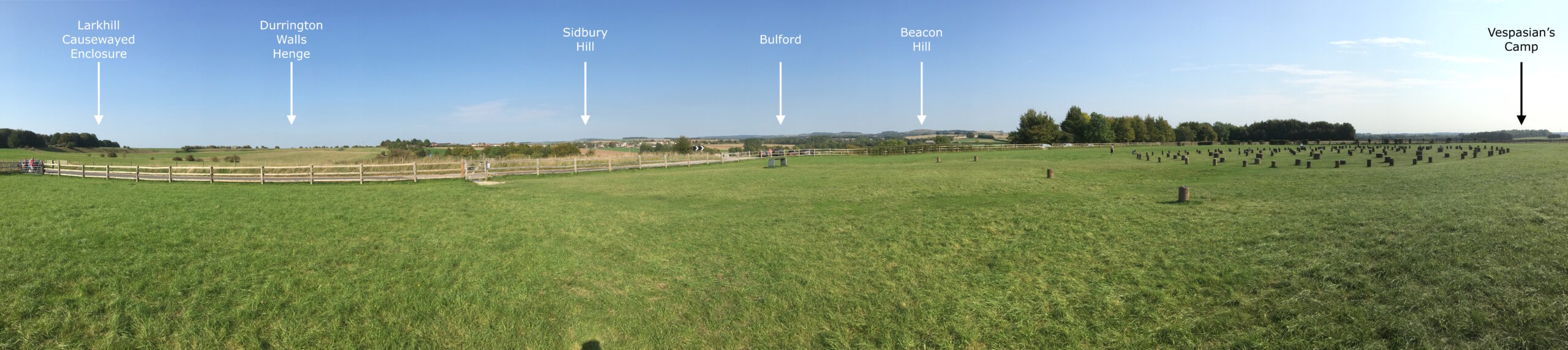

But for now, I’m going to draw your attention to this great sweep of eastern horizon. (Click on the panorama of the Eastern Horizon above). Ranging in the north from the Larkhill causewayed enclosure, discovered in the last couple of years by an archaeological evaluation ahead of some new military houses being built to the eastern end of Larkhill Ridge.

Larkhill Causewayed Enclosure, 2016 Click to enlarge. Photo: K A Freeman

A causewayed enclosure is essentially an area of ground that is delimited or marked out by a series of one or more concentric banks and ditches with breaks in the banks and the ditches. The causeways allow people to go in and out of the central area.

And they date, well, this one particularly, dates from around about 3,700BC. So, we are 5,500 years ago. And this is the time of the early Neolithic. And our best understanding of them at the moment is that they are seasonal gathering places for people to come together and meet and exchange news, goods, partners and whatever else.

There is another causewayed enclosure on the Larkhill Ridge. It’s about two and a half miles west of the same ridge and it’s called Robin Hood’s Ball. And Robin Hood’s Ball and the Larkhill Causewayed enclosures maybe two of a pair. Robin Hood’s Ball overlooks the Stonehenge landscape. In fact, it’s inside of Stonehenge up on the far ridge line from Stonehenge’s point of view.

But Larkhill Causewayed Enclosure looks in a different direction. It looks out to the east. It looks over the Avon River valley to the far horizon beyond. And it’s this horizon that I’m going to describe.

Larkhill Causewayed Enclosure and Durrington Walls Henge. Click on the image to bring up the whole annotated panorama.

Durrington Walls Henge and Sidbury Hill. Click on the image to bring up the whole annotated panorama.

So, Larkhill Causewayed Enclosure in the north, and as we swing around to the right a little closer in the foreground you can see the ditch and banks of Durrington Walls. The Northern side of Durrington Walls. And that great green scarp up there is not actually the bank, that’s a natural feature. The bank was on top of that feature and the ditch was at the bottom of it. And Durrington Walls Henge is absolutely huge. In diameter it’s over 400 meters across and that ditch that produced the materials to create the bank is incredibly deep. Five to six metres deep, 18 metres wide across the top, and excavated we believe in something like 22 distinct sections. Some researchers have suggested that it might even have been completed in one season. So that gives you some idea of the enormous amount of people who would have been needed to carry out that project.So, as we look over Durrington Walls and we look across the A345 we can see the other side of Durrington Walls on the far side of that road. And in the distance on the skyline we can see Sidbury Hill.

And Sidbury Hill is a very important landmark on this horizon. It’s the site of an Iron Age hillfort, but there are signs that there have been activities up there that predate the Iron Age. Certainly, there are three Bronze Age long distance linear ditches that converge on Sidbury Hill. Behind it is there is a magnificent Bronze Age barrow cemetery called Snail Down. And Sidbury lies exactly on the summer solstice sunrise line as seen from Stonehenge.

So, if you are inside the circle of Stonehenge on June 21st and you look out past the Heel Stone and along the line of the Avenue that stretches off towards the North easterly direction over Larkhill then after about seven miles you intersect Sidbury Hill. And the summer solstice sun today if you stand on Larkhill on the alignment that sun rises out of the Southern flank of Sidbury, and it’s a sight to see.

Sidbury itself seems to have been the focus of other parts of the prehistoric landscape which we will come to in a minute. In front of Sidbury from our point of view you can see in the sort of the three quarters distance a copse of fir trees going up a slope from left to right. And that is Silk Hill.

And Silk Hill is the site of another Bronze Age barrow cemetery of some spectacular mounds including one that looks for all the world like it really ought to be called a henge with a barrow in the middle. It’s a very large banked and ditched area in the middle of this barrow and it’s unlike any other barrow that I’ve seen. It’s classed as a barrow, a bell barrow actually, but I have my doubts on that one.

My favourite barrow cemetery- Silk Hill on Salisbury Plain – Bell, Disc and pond barrows here #MuseumsUnlocked pic.twitter.com/D3zK0qbREV

— Richard Osgood (@richardhosgood) April 25, 2020

In front of Silk Hill, a little to the left, but still in line with Sidbury we have Barrow Clump behind the village of Ablington, which is yet another Bronze Age barrow cemetery but there is only one upstanding barrow still remaining. And that was excavated in the last few years by a Ministry of Defence team, Operation Nightingale because the barrow was being destroyed by badgers burrowing in and throwing out human bones.

So, the decision was taken to excavate the barrow entirely, and we excluded the badgers, to discover what it was all about, then rebuilt the barrow and let the badgers back in. And the Barrow Clumps barrow proves to be totally unexpected in the finds. It originates as a Neolithic site probably 5,500 thousand years old as a cairn without any obvious burial, which is then overlain by a Bronze Age bell barrow with remains.

But subsequently, and a long time subsequently, it was used by Anglo Saxons in the area as their grave yard as well.

Wonderful evening celebrating the launch of the Barrow Clump publication!

Some of the incredible Anglo-Saxon finds (and a few older) will be on display in the Museum tomorrow and Saturday. We’re also offering half price tickets to Service Personnel + families. pic.twitter.com/sB0qaWNO68— Wiltshire Museum (@WiltshireMuseum) January 9, 2020

And around about 100 Anglo Saxon graves have been found immediately surrounding the barrow in Barrow Clump. And some of these are warrior burials with Saxon shield bosses, iron shield bosses over their chests with spears and all the usual weaponry that you would associate with warriors including a seax, an Anglo-Saxon sword, a very rare find indeed.

Some pics from Barrow Clump this weekend @BreakingGroundH Please share as needed pic.twitter.com/4wvNeTudOm

— Occy (@gsd1979) July 17, 2018

So that spot just up there at Barrow Clump seems to have been an important place from around about 3,500 thousand BC to around about 600 AD. So, for more than 4,000 years people have paid attention to that particular spot.

And all of those, Barrow Clump, Silk Hill, Sidbury Hill and Snail Down beyond, are all roughly in a line from our point of view where we are standing in this part of the landscape.

Moving further across to the right we start to intersect the trees and the valley of the Nine Mile River. And this is a winterbourne that rises on the east of Salisbury Plain and flows down to join the Avon in Bulford. And at a site of some more army houses newly built in the last few years in Bulford was discovered another unexpected find. A huge collection of Neolithic pits.

These are far smaller than the Durrington Pits that we’re going to talk about. These are only about a meter or so in diameter and a meter or so deep. But into each of these pits had been deliberately placed certain things: arranged deer antlers, carved chalk balls, about the size of tennis balls, deliberately carved into spheres.

We were fooled too but it’s not a snowball, it’s a Neolithic chalk ball, recovered from excavations at Bulford. Find out more about the site and its fascinating finds here: https://t.co/0OJBESzVk6 #ArchiveCalendar #AdventArchive #advent #christmas #archaeology #snow #chalk pic.twitter.com/nUzO8MWkmZ

— Wessex Archaeology (@wessexarch) December 3, 2018

Pottery. Half a pottery vessel in this pit, and the other half of the same pottery vessel in another pit. As well as flint, that’s worked flint and tools. So this is interesting. Near to these pits is a flint industry working area where clearly people were paying a lot of attention and time to creating flint tools. And it’s fairly early Neolithic as well.

The style of pottery discovered there is Woodlands style from around Durrington Walls and the type of flint seems to be predominantly that which you can only source from Sidbury Hill. And that probably explains why this area focuses its sort of gaze up the winterbourne valley in the direction of Sidbury Hill. It seems to have been important for those people in the Neolithic at that spot.

And just to mention in passing there were also dozens more Anglo-Saxon graves in the same area of the army housing that was being built along with a practically unique feature, a double henge, which is a pair of intersecting earth work circles. As I say almost unique. We do not have an explanation as to what it means but in this same settlement industry area from the Neolithic that focuses out looking towards Sidbury Hill. And all this activity is going on, on the other side of the modern road, Double Hedges, within sight of a once standing sarsen stone called the Bulford Stone. And it’s no longer standing. It’s now fallen over lying in an arable field but what we know about it is that it has always been on that spot. We found the solution hollow for the Bulford Stone where it formed within a couple of meters where it lies now and that solution hollow is separate to the stone hole that was dug by the people who once set it upright.

Also very close by to that sarsen is a Beaker period burial with some very interesting grave goods including a quite rare transparent rock crystal. So, all that area is right there just between us and the horizon concentrated together from the Neolithic through to Bronze Age and later to the Anglo-Saxon era.

Then we move a little bit further to the right and if we pass over the top of Woodhenge we start to meet on that far horizon the ridge line of Beacon Hill. And its older name is Haradon Hill. And this has also got lots and lots of Bronze Age barrows along the top of it. It has long distance bronze age linears that run up to it, there’s a long barrow on the side and the range road leading to Tidworth in that direction as well, so we are early Neolithic again. And as we continue to the right and start to look more generally due east, we start to climb the ridge towards Beacon Hill. At which point we seem to have run out of prehistoric remains. And Beacon Hill is the very tall hill that you can see directly in front of us to the east that has a pair of radio masts on the top. And one on the very top of it. And the A303 runs just at its base at the right-hand side of the hill.

Woodhenge Eastern Horizon: Beacon Hill and Vespasian’s Camp Click to see annotated panorama in full.

So, Beacon Hill. Is it a magic mountain being the tallest spot around, taller even than Sidbury? Is it somewhere where the general population aren’t allowed to go? Is it the abode of the gods if you like? We don’t know. We can speculate about it, but what’s interesting is that ridge line just to the north of Beacon Hill seems to be what the Stonehenge greater cursus is targeted on.

The Stonehenge Greater Cursus, a mile and three-quarter long monument – we’ll see it later when we get up to King Barrow Ridge, runs roughly east west. But not sufficiently accurately to be viewed as an equinoctial marker lined up of the sunrises and sunsets of the equinoxes. In fact, most researchers now think that what it’s doing is drawing attention to ridge line north of Beacon Hill. So, clearly, we’re referencing the limits of our vision in the landscape from places that are more central in the landscape.

And as we go to the right of Beacon Hill and we start to head towards the south east, then we cross Hara’s Barrow on the southern flank of Haradon Hill. Hara’s Barrow is an ancient name perhaps giving its name to the Harrow Way, which is what the A303 once was called before it was a large road and was only a drover’s track.

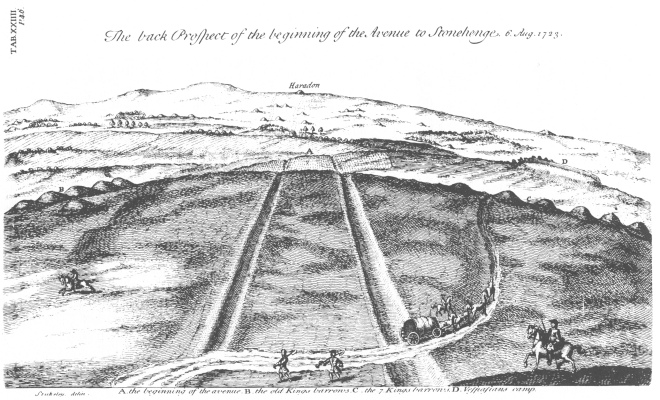

William Stukeley drew Hara’s Barrow in some of his landscape illustrations in the eighteenth century. Very good landscape illustrator and he thought that the Stonehenge Avenue when it reached King Barrow Ridge turned and was targeted at Hara’s Barrow. Well, he was right that it turned and faced in that direction but it doesn’t go straight towards Hara’s Barrow. In fact, it then curves to the south and ends up in West Amesbury.

But Stukeley’s work is so good that we still refer to his drawings today and pick out the same features in the landscape that he illustrated for us, and know exactly where he was standing and what he was looking at.

To the right of that we have Boscombe Down military air field. Very nice Bronze Age barrows inside there that you can’t get to any more unless you’re military. Then we come to Amesbury. This sprawling town that’s in front of us in a south easterly direction. Some big aircraft sheds and Solstice Park industrial and retail area are full in view as we creep across more southerly over Amesbury we eventually come round almost due south of us to a forested, or wooded hillside called Vespasian’s Camp.

Vespasian’s Camp. Vespasian’s Camp is named for the Roman general, Vespasian, by people that thought it was a Roman camp, and they were wrong, is actually an Iron Age hill fort again with earlier activity on the site. There are Bronze Age barrows and the sites of Bronze Age barrows running across its top. It’s a chalk spur that sticks out in a meander of the Avon in Amesbury. It’s a very nicely defendable spot. And just on the northern side of it, between the chalk spur and the current A303 is perhaps one of the most important spots in this prehistoric landscape. Certainly, one of the most long lived and that’s a site called Blick Mead.

The Spring bubbles up at Blick Mead, River Avon. Click to enlarge. Photo: Kate Freeman

Blick Mead we now know after ten years of excavation is a Mesolithic settlement site. There’s a spring that arises from underground, a chalk spring, that creates a pool, and because the water comes up through the chalk from below it’s at a constant 110 to 150 centigrade and it never freezes. So it’s a highly dependable clean, fresh, water source, exactly the sort of thing that hunters and gatherers would go to as a resource spot as they travel around their territory following perhaps migrating herds of deer or aurochs or whatever else.

People have the idea that hunter gatherers wander about looking for hazel nuts and are very hungry all the time, but it’s not the case. They know where the resources are and they move from camp to camp following the seasonal availability of these resources, be it animal, or vegetable, or water, or shelter. And we know from the radiocarbon dating evidence that’s been uncovered at Blick Mead that people returned to that same spot for about four millennia, from about 8,000 BC to round about 4,000 BC give or take. People endlessly came back to that same spot time after time after time.

Perhaps because Salisbury Plain area where we are now would have been an excellent spot to hunt aurochs. They like wide open grasslands as the Plain would have been at the time. It’s never been forested since the Ice Age. It’s always been open, scrubby, I hesitate to say prairie-like, grassland. It’s not big enough to be a prairie but open landscape just where large herbivores like to be.

Aurochs: In case you don’t know what an aurochs is, it’s a primeval cow and a normally sized adult is around about two tons, six-foot-tall at the shoulders with long horns, a four foot long span of horns at the front and capable of about 40mph. And if you can manage to bring one down and kill it, it will feed your extended family for about a month. And we’ve got very good evidence from Blick Mead that the people were consummate hunters of these animals because we’ve got cooked aurochs bones from the excavations around the spring. And one of those bones is an aurochs ankle bone in which is embedded the tip of a flint spear or arrow. Presumably if you are being chased by a 40mph angry cow that weighs two tons shoot at its feet to bring it down.

So, from north to south we go from Larkhill causewayed enclosure to Vespasian’s Camp. In terms of timescale, from Vespasian’s Camp we’re looking at least at 10,000 years ago as we swing round from Bulford, where Anglo-Saxon 1,500 years old, where Bronze Age 4,000 years old, we have Neolithic context 5,500 years old, and beyond. So are dealing with an immense span of time and an immense span of area. And this is just 1800 of the eastern horizon.

I sometimes ask people where they think the centre of the Stonehenge World Heritage Site is. And quite often they’ll say “Ooh it’s Stonehenge”, or “it’s Woodhenge”, or “it’s Durrington Walls”, and for me I don’t think that quite works. I think the centre of this landscape lies within the hearts of the people who experienced it, going all the way back to the end of the ice age. And coming all the way up to today, with the visitors who are wandering about, and experiencing it now. Every single part of it, once upon a time, was a continuous landscape. Not broken up by modern housing developments, or roads, or fence lines or postal districts, but instead was a continuous whole, and it didn’t stop at the horizon that we can see to the east. It continued beyond that. It continued in fact across the whole of these islands. And before about 6,000BC it continued across all of Europe, which means then all of Asia, which ultimately means all of the world is this continuous special landscape.

And as we think about what these pits that have recently been discovered at Durrington Walls might signify I’m going to point out that certain points in this landscape, parts of it are framed by the arc of these pits almost as if it’s attempting to keep its specialness to the east uppermost in the minds of the people. They might have been making walks, pilgrimages, who knows across particular routes through the Stonehenge landscape. And we’ll see a little bit more about that as we walk around along this old railway track up to King Barrow Ridge, where we overlook the ultimate destination for some of those people which is that famous stone circle. Thanks for listening. Let’s carry on to our next spot.

Part two is a video of the group walk from the Durrington Walls area up to King Barrow Ridge, past some of the giant pits. Simon will explain how the sample pit could have been understood. To be published.

© Text Simon Banton

Simon Banton works as a freelance guide for tours of the landscape and the monument itself. If you’d like him to show you around, please get in touch here and he can work out a bespoke itinerary, starting out from the Visitor Centre.

Please share